ARTIST: Mobai

Interview & Text: Luxi

DATE: 2023.10

Moonrise at Ito

Wabi-Sabi, Natural Interactions, Framing Experiments, Intimate Perspectives

Introduction

Mobai grew up in Fujian, and is now based in Beijing and Ito, Japan.

She graduated from China Academy of Art, Chinese Painting, and is now known for her Wabi-sabi painting that chants prose on rice paper.

Mobai’s works derive from the subtle, private or impersonal moments, and they are usually subject to a long natural process that results in the paint to be wet and peeled off. Her work invites

the rain, the river, the air, the vegetations, and the geology to work on the fragile rice paper, and the temporal marks are further echoed through the texture of rice paper, wooden frame, and

the terracotta paint in ceramics.

Following is a conversation we had with Mobai in late September, about painting, writing, photography, about books and book design, and also, about waves, about trees, about the long walks,

the moonrise.

Mobai’s works have been exhibited in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Taipei, Osaka, and Paris.

AYA: Mobai, are you based in Beijing and Japan?

MOBAI: Most of the time it’s Beijing. Izu is more like a vacation house that we occasionally visit.

AYA: But the vegetations we see in your painting, the mid-night-like color temperature, it reminds us more of the Southern provinces in China instead of Beijing?

MOBAI: That’s correct, I actually only came to Beijing for college, but it’s been more than a decade now. In Japan, the region I live is called Ito. It feels like a combination of the Chinese South and North. I’m originally from Fujian, where the land is burdened with heavy vegetations growing relentlessly in the humid weather. And the weather, burdened as well with cloud. Clear days were a rarity. Ito has the vegetations similar to South China but also with more clear days throughout a year. I guess that’s where you can trace the vegetations and weather condition on my canvas.

Izu, Japan, image provided by Mobai

AYA: Speaking of South China, in literature there’s a new genre associated with this geographical and cultural region, and we call it Southern Literature. Many of the important writers in this genre like Chuncheng Chen (陈春成), Zhao Lin (林棹) are also from Canton, Fujian. Their writings absorbed the mystical names and vegetations the writers spotted while taking a walk. Similarly, in your painting, we also feel the resemblance of the meandering rhythm and intimate perspective of a rural flaneur. To take a walk in the rural wilderness – is that where you came from?

MOBAI: I don’t like to walk around on my own. I need someone to propose a walk first. And when someone indeed proposes a walk, I will usually enjoy it quite a lot. Have I made myself clear? If you ask me to take a walk outside, I’m usually willing to do it, and to do it for an elongated time.

image provided by Mobai

I remember all the long walks we have taken when living in Japan. The place we stayed was a fairly minor town at the back of the mountain, and our house was halfway up a small hill. I was preparing for a new series and my husband was there with me. I started painting every morning and wouldn’t stop till slightly past the mid-day. Around 1pm or 2pm we had our light lunch and took a walk in the late afternoon. We usually walked to the other side of the mountain where there’s a viewpoint. We walked very slowly, slowly passing by the tiny playing field, the scattered houses, and then a basketball field, a football field. Further up, you would see the starting point of the cable cars, and then a small park. From there, the trail narrowed down and was usually covered with moss, shrubs most time of the year. The trail would lead you to the deep forest and all the way up to the summit. When we arrived at the summit, it’s usually the sunset hour. And duet with the sunset, the moon also rises. At the view point, you can observe the moon rises slowly, steadily. Your mind was always there, and also not. We would talk for a while till all the light evaded us and slowly felt our way back home. At the foothill, there’s a tiny bistro, or probably not even a bistro. We usually had our dinner there, and then slowly walked up the hill where our house was located.

image provided by Mobai

I still think a lot about the long long walks I have taken. Within the timespan of a late afternoon and evening, so many things would flow into you, all the way into the night. The sun and the moon have their nocturnal weight. Our house harbored us at night, and there’s usually several hours for evening TV show. That’s the walk I can think of, the dearly scenes, dearly rhythm, and consciously or unconsciously, they are in my work.

image provided by Mobai

Flowing Frames

AYA: Throughout the different series you’ve painted across the years we can notice there’s an on-going experiment with the concept of frame. Sometimes the background wall also becomes an extension of the canvas, sometimes the painting overflows beyond the framing boundary, and sometimes the frame also dissolves into the canvas. When did you first start the experiment with the frame?

MOBAI: I think the farthest my memory can go is back to the time when I was preparing for my B.A. thesis. From that time forward, my frame started to take on a different metamorphosis than what’s traditional in my genre. At college I painted mainly with fine brush and loosely woven silk. The loosely woven silk is a delicate, semi-transparent material, and throughout the whole process of painting, we will just stretch the silk unframed, hold it against the light, and that’s where you can observe how the paint is slowly soaked up by the minute surface texture with a slight fat-like shine, while also maintaining a fragile thinness. But the routine process afterward is that you will lay the silk on top of a rice paper and frame it. The fine, fragile texture I observed in the process will soon be gone after the framing, and the colors are solidified, deprived of their flowing suggestiveness.

Blue hidden underwater, Mo Bai, Signs, 2020.

Therefore, when it came to the time of preparing my own B.A. thesis I really wanted to find a way to maintain the thin fragility in finished paintings. I still painted on the loosely woven silk, but at the time of exhibition, the silks were hung completely unframed and without the contrasting rice paper. In order to make it work, we created a stand, and the silks were attached to the stand with strings that were left suspended. There was a contrasting background but kept a long distance away from the painted silk – the similar distance as you would have during the painting process. And of course, the lighting was also deliberated and functioned to bring out the semi-transparency of the silk base. During the whole process I worked closely with the framer: I came up with the idea and he tested it for practicality or looked for different ways to achieve the effect. In retrospect I feel it all started with the dissatisfaction I have with the traditional framing.

image provided by Mobai

Though having worked with extremely skilled framer, the whole process was still very time-consuming. And every work was of a different size, and every size entails different handling. Gradually it became clear that it’s not practical nor financially-wise to work with a framer in the long run, and that I have to deal with the frames on my own. That’s when it started to become excitingly experimental, and frame became a fertile field for many new ideas. For the first several works, it’s just simple frames but specially painted to be aesthetically coherent with the painting. I realized people did like the painted frames, and I went further to expand my paintings onto the frame, to make the frame part of my extended canvas. In the later series, I have also tried narrowing down the frame, turning it into a miniature or singling it out and giving it back onto the canvas as a structural element. In whichever way my intention is always to hold the frame and the canvas in an organic harmony. I don’t like it if the frame stands out abruptly or being completely ignored, I want to reconsider the possible relationship between the canvas and the frame.

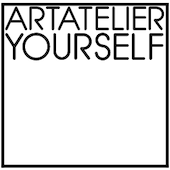

Watching Light Maneuver Outside the Courtyard, Mo Bai, Vita with a View, 2022.

My present works do not strictly fall within the category of Chinese painting, but neither can they be categorized as Western oil painting. I paint on rice paper, and there’s something from Chinese painting in it, something exists in the form of oil painting. Among the extant methods there isn’t a perfectly compatible framing for me, and this requires me to constantly experiment.

image provided by Mobai

AYA: With the highly experimental frames in mind, it seems that your works pose a challenge to the exhibiting environment in terms of light, of its aesthetic interaction. In your mind what is the ideal exhibition room?

MOBAI: When I’m preparing for a specific exhibition I will constantly think about the physical environment of the exhibition room. What is the light like in the room? Will it fall on my paintings from aside or fall as a pale lighted spot? How does it feel like, solemn or relaxing? And I will also imagine my paintings being in the environment, being hung there against the wall – what will it look like? There are two different walls in my studio, both textured, but one light and one dark. And I also visualize my work against a white-washed wall. There was a series in which I just left half of the paintings empty, and the emptied half was either glass or hollowed-out. When this series was placed against the wall, the wall would become part of the painting, and the completion of the painting thus became interactive with the environment. Leaving blankness is a traditional technique in Chinese painting, and I want to make a physical blankness, a factual blank space that allows the painting to pick up part of the environment.

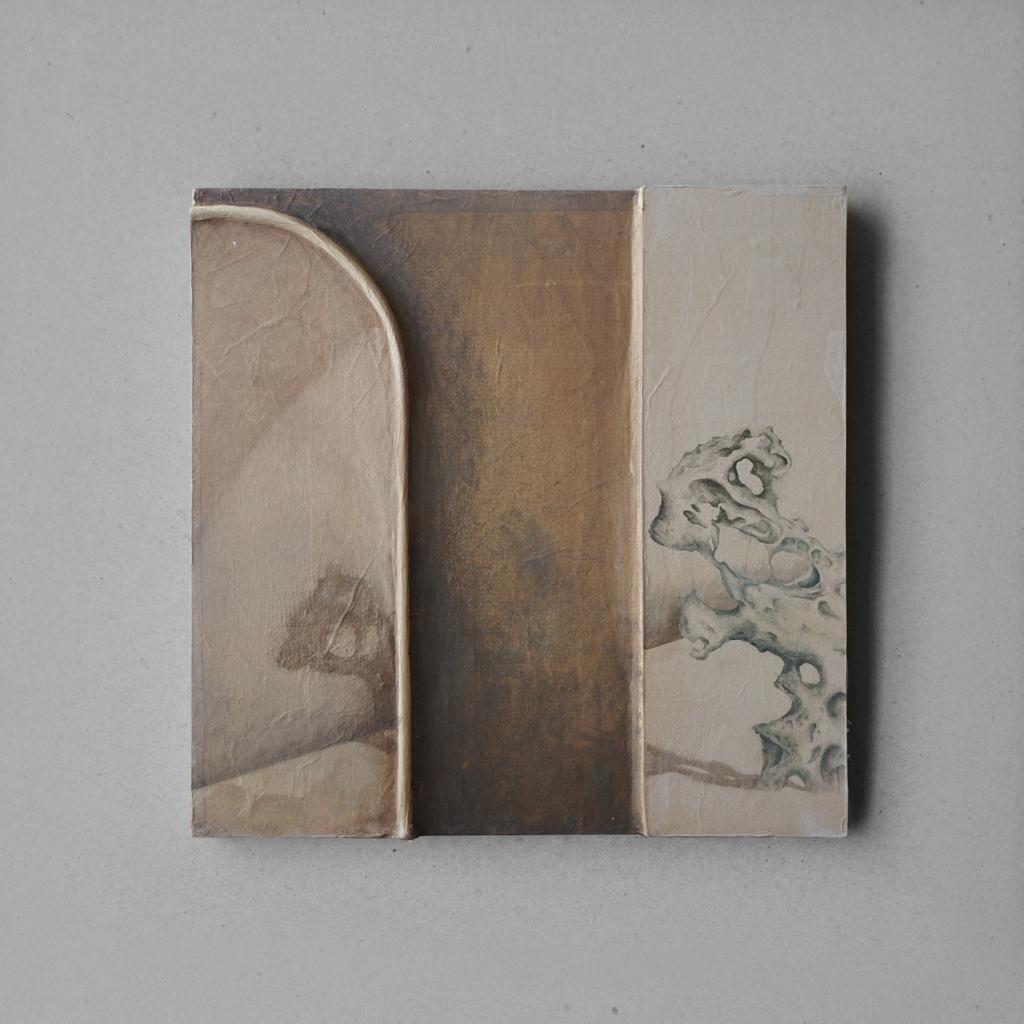

Echo Under the Dome, Mo Bai, 130 x 180cm, 2022.

Worn, Wet and Torn

AYA: We’ve noticed that in your oeuvre there are very few large-scale paintings and most of the works are in mid or small size. What is the reason for that?

MOBAI: I think for my own capacity of visualizing and taking control of the scene, mid and small-size is the medium I feel most comfortable with. And for small works there’s a shorter trajectory to bring your visual experiment into completion, and it requires less time. It’s a way to rapidly try out different things. On the other hand, large-scale works and the process of creating them indeed pose some physical challenge for me: to move them around, to try and erase color, it’s all difficult to me. My own method is to conduct multiple experiments on small size works, and if the experiments turn out to be sensible and repeatable, I might carry them on to large-scale works. And of course, the cycle of finishing a large-scale work is usually very long; the number of large paintings I can finish within a year is extremely limited.

For me there isn’t a gender connotation in the scale, as people would usually assume. It’s just how rapidly you can carry out your initial design. And personally I also need to shift between different scales in order to maintain an equilibrium for my creativity. If I have been engaged with making large paintings recently, my thinking towards the scene and theme tend to be heavier, more serious, and more contemplative. And in comparison, making small size works usually allows me to be flexible, whimsical. The creative mentality involved is also drastically different.

What Thou among the Leaves hast Never Known,Mobai, 16.5 x 28.5cm

Usually after completing the frames for large-scale works, I will have an impulse, a strong desire to realize what I have visualized, and the frame is also there to work as a reference, a seduction. My large paintings usually start from there. Most of the time I will come out of a large painting fairly exhausted, and with a burdened mind that’s been engaged with heavy thinking and laboring for a long time. The highly disciplined mind calls for some small paintings to loosen up, to mess up; it allows my mind to go back to a comfortable balance. And after several months solely with small paintings, there will again rise an impulse for the big paintings. The circle goes round and round, and that’s the clock I find works for me most.

image provided by Mobai

AYA: Small size works are like slice, paragraphs that contain private time and fragments. And when Edgar Allen-Poe discuses short stories, he also brings up the famous principle of “single sitting” – mainly that writers should limit the length of short stories within what a reader can finish within one sitting. And to bring that principle to painting, if that’s ever comparable, is the creation and appreciation of small paintings also something that can be finished within a single sitting? Do the small paintings mean a complete, immediate presentation that’s freed of repetition, alteration, erasing and covering throughout time?

MOBAI: I’m more like the opposite of the immediate presentation. Going back to my works, there are many marks, many layers of marks on the canvas. They cannot be finished immediately within one sitting; they are like an old wall that has to undergo years of tossing. No matter it’s to paint and then wet, or to tear and mend a certain part, in order to have the natural marks you can see at the end the painting has to go through an extensive amount repetition, erasing and alteration. There is the lengthy process, and then it leaves the natural marks. All the textures in my work come from paint and tear and tear and paint, all the way till the very end. For this reason, I might work on several different paintings at the same time at first, and immerse myself in a single work when it’s at the final stage.

Leaving My Weary Heart, Mo Bai, Fluttering among the Gods, 2022.

AYA: The wetting, tearing, and wearing, are they also part of the design?

MOBAI: Yes. When I first started painting something like the Wabi-sabi I actually had no idea about how it should begin, and for some reason very accidentally the nature intervened. I was halfway through a painting and left it outdoor when in the afternoon there unexpectedly came a storm. When I returned to my studio the next day, the painting was wet and naturally dried again. Some of the paint has fallen off, but fallen off in a very beautiful way. This accident might be the inspiration. I like to go back and forward, to paint layers and to tear, wet and wear them. It started as something accidental, but it now becomes my technique.

image provided by Mobai

Image/Words

AYA: For some reason, when viewing your work, viewers often pay an equal attention to the title of each painting. But title might also fail to grasp how the words work here. The words are like an accompanying text, an ending footnote, or a slow sign on time from the painter. They create an echoing with the painting that also feels like coming from the pre-painting. How do you imagine the words given to each painting, and how do you imagine their effects?

MOBAI: Most of the titles/words were only given after the painting’s completion. A few were vaguely conceived during the process, and some were thought of afterwards. I want to have a poetic title, a title with the blankness of a verse. And I want my work to contain the blankness, to be less substantial, and less dense. The title amplifies the blankness in the painting, so to speak.

I can never paint based on a passage of words. Every artist has their own method: some can go from abstract to concrete, but it’s the opposite for me, I have to go from concrete to concrete. The imagery, the light and shadow I need won’t walk up to me from abstract, but when the work is completed, I also need something to compliment with the concreteness. In the best case, it’s the verse with some blankness, it reduces something from the painting.

Usually, based on the trope or theme of the exhibition I will constantly look for myself the creative core, and once I hit the core the whole series can go on. Some series go around a poetry collection, some around a very vague, rough imagination that was later developed into a whole series. But it is always the vague notion instead of a fully developed idea that carries me forward in painting. I would like it to be a bit empty, to be ethereal and playful. And for a series, as long as they’re sensible being alongside each other.

image provided by Mobai

AYA: Speaking of poetry collection, literature seems to function as the silent, distant background here in your painting. They function like a light condition, but the actual form of their function is hard to be traced on the canvas. Several years ago, you named one of your work “Woolf’s Waves”, and later you changed the profile photo of your social media account with a photo that reminds people of Lily Briscoe from To the Lighthouse painting on the shore rock. How do you see the influence from literature?

MOBAI: I am not a serious literature reader in any sense, and the passion for reading you had as a teenager or in the twenties has long left me. I used to read from cover to the end, and books used to cast a deep impression to me. But I can barely read like that in recent years. My reading right now is more like going through several pages and leaving it be for a while, and very randomly when it feels right I will return to the book. It’s not an unstopped, serious reading, it’s more like when I am painting, much scattered and loosened up.

image provided by Mobai

I like The Heart is a Lonely Hunter as a kid, but that one I have read a long time ago. Later I grow to like Michio Hoshino, a Japanese photographer, and that’s when I started painting. He is capable of relaxing me down, he has a perspective I can understand without any mediation, and all his scenes I can see them through the words. I am not sure what other people feel like when reading Hoshino, but this transition is very natural and most intuitive for me, a very easy read. In the past several years when travelling was made difficult by Covid, I also returned to him.

The other book I’d like to mention is Wim Wenders’ Once. Like Michio Hoshino, he also writes as a photographer. The book is mainly composed of fragments, fragments that resist going into the deep water, and accompanying the words are his black and white photographs. There aren’t that many texts or photographs, and a large blankness is embodied. You can read the blankness, or choose not to, and it feels good to me. And I recently discovered it is out of print, and it feels even better.

image provided by Mobai

The Joy of Talent

AYA: In almost all of your interviews talking about painting you feel very at home. Can we assume that’s how you feel also at work? Has painting ever been difficult to you, and have you always been able to feel at home?

MOBAI: If it’s only painting, it’s not very difficult to me. I think the difficult part is in life.

With that being said, I also had my years of mere practicing like it’s a hard labor. My dad is also a painter and a calligrapher. When I was a kid, whenever it’s a summer break or any days off, it’s a requirement that I shall paint or practice calligraphy on top of the regular schoolwork. I am required to write the calligraphy even if I don’t know the characters. Years after years, it’s always like that, and I have never been excited about summer or winter breaks. I didn’t understand what all this was for, and of course, I complained, I fought, I tried to talk with my dad, but nothing could be changed. I kept writing calligraphy all the way till I was 18, that’s the year when I applied to China Academy of Art and got in. I have always been very grateful of all those years, of having started at such a young age to paint with brush, and I know if it weren’t for my dad I might have stopped halfway. Later on, I have taken the transition from calligraphy to painting, and it has been very smooth thanks to the early years of meticulous practicing under the instruction of my dad.

image provided by Mobai

AYA: And after the transition into painting, how does things go? Were there any periods when you were unsatisfied with the way you’re working?

MOBAI: yes, there definitely were. At the beginning, you know you want something, but this something is very vague and its configuration is not yet clear to you. Meanwhile you knew very clearly the thing you want was not what you were at that moment. This process is tormenting, but still I think it is essentially good to have the desire. It points out what’s not good enough about you, and to know you want something, to try to reach it, it’s all very important to me. The process is a torture, but the torture will clear out.

AYA: How did it clear out for you? Was it by trial and error?

MOBAI: Sort of, but more like through expanding the knowledge and notion. I used to stay only within the inner circle of painting and focus only on my own work. I was very ignorant about other genres and the artists who engage themselves with other media. A friend of mine who’s doing ceramics pulled me out of this, and it was through her that I realized there were many more materials that I can learn and work with on my painting. It feels like obtaining a key, and when you have the key it naturally clears out. I become conscious of where my talent lies, and the use of the newly-adopted materials is an exciting thing I have never tried before – and it works out very easily. It feels very good to have cultivated your own small lot of creative land.

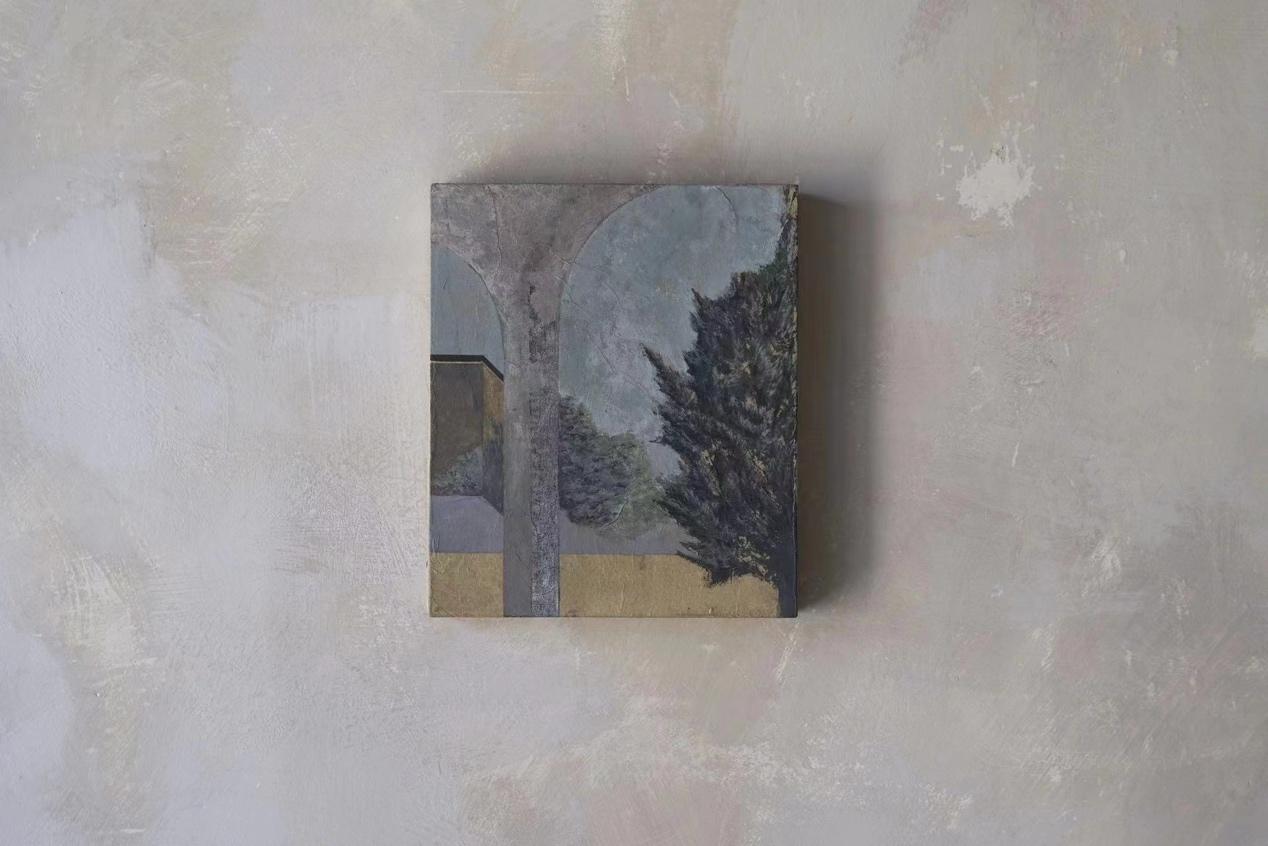

Yín Zhang,Mobai, Archipelago, 2023

AYA: So there is a clear self-consciousness when you arrive at where your talent truly lies?

MOBAI: Yes, you will feel it is smoothly easy and exciting to do things. When you finish your work every day, you immensely look forward to returning to your studio and continuing working on the painting the next day. It’s a very pleasant process. I was co-sharing a studio with my artist friend, and my friend can sense that I’ve found what I want. Actually, I have had doubt before. I am not sure whether I paint because I truly like painting, or I paint merely because I can paint. But when I found the tiny spot that affirms my talent, I think I know.

image provided by Mobai

Mobai's Past Exhibitions

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2023, Paris, Lignes et Lumières

2022, Shanghai, Fluttering among the Gods

2022, Hong Kong, Slightly Cold, Colored the Branch

2022, Beijing, Listen

2022, Taipei, Echoes Under the Dome

2021, Taipei, A Silence View of Corner

2021, Xi’an, Vita with A View

2021, Osaka, Beautiful Dream: Yuta Nishiura x Mobai

2020, Tokyo, View

2020, Shanghai/Beijing, Vita with A View

2020, Online, Signs: A Parallel Moment

2019, Chengdu, Wilderness of Life

2018, Saffeon Sea, Evaporate · Special Exhibition

2019, Hangzhou, Signs of Inner World as Outer Space

2017, Hangzhou, Mountains on the Horizon

2017, Beijing, Evaporate

2015, Beijing, Edge of Blue

2009, Fuzhou, Birds Dress in Finery

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2023, California, Archipelago

2022, Shanghai, ART021 Shanghai

2022, Taipei, ART TAIPEI 2022 / ARTNUTI GALLERY

2022, Taichung, Art Shinchu

2022, Shenzhen/Beijing, Ever-curious · MICKEY the true original exhibition

2022, Taichung, Asian Contemporary Art Group Exhibition

2022, Taipei, One art Taipei

2021, Shanghai, Unknown Zone

2017, Beijing, Women of the world: an exhibition of contemporary Chinese female artists