ARTIST: Andrew Orloski

Interview & Text: Luxi

DATE: 2024.06

Stone, Fire, and Iron: The Ghost of Materiality and a Sculptor’s Labor

Sculpture, Anti-elitism, Cast, Arts and Industrial

Introduction

The first time I met Andrew it was via email – he was preparing the installation of his upcoming exhibition, and I was cc-ed in the email as a member of the gallery team. The first email

was a technical note, informing the gallery of the physical details necessary to install the sculptures at a particular angle, which entails a heavily industrial process like drilling deep

into the ground, preparing the wall for some heavy duties. I felt like being transported to an unfamiliar section at Home Depot, and it was from that email that I knew very early that Andrew

Orloski would be a substantial artist – substantial in the sense that a grandmother’s beef stew brings substantial joy, and in the sense that a molecule is a substance of perplexity.

A year has passed since the exhibition that introduced Andrew to me, but the substance, and the glance into the heavily laboring material world linger. Therefore, we had an interview, an

interview that discusses some dangerous questions, an interview that’s possibly hard, but also not lacking in humor and poetry.

Andrew Orloski Studio Visit(video provided by Andrew Orloski)

Where Sculptors Stand in a Class War of Labor

AYA: Compared with artists of other media, sculptors seem to be a group of more mystery and myth: not only is your training drastically different from typical modern art school, but also some of the skills required in your practice may even be unattainable from a traditional program. So Andrew, can you please unveil the myth for us a little bit and tell us briefly how did you become a sculptural artist?

ANDREW: My journey into sculpture began many years ago during my undergraduate years from 2005-2010. Initially pursuing a degree in painting, I stumbled upon a bronze casting class that

sparked my fascination with the material world and the narratives it holds within three-dimensional objects.

After graduation, I landed on a full-time position at a fine art foundry in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, near my alma mater. Working in the foundry was demanding, often hazardous, and physically

taxing, but it provided invaluable hands-on experience in bronze and stainless-steel casting and all the many processes that are involved in them. Transitioning from the structured and

experimental environment of academia to the fast-paced world of professional fabrication was a stark adjustment. Each task demanded unwavering attention to detail and precision with no room

for error. I was one of the only people in that foundry entrusted with a diverse array of responsibilities, from molding to metal finishing to pouring bronze, and I never knew what I was going

to do on any given day entering work.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

It is fair to say that during my time there, I learned the importance of extreme precision and getting things right from the start. Working under such pressure wasn't easy, as mistakes could

cost me my job or even incur some physical jeopardy. However, it also provided me with the opportunity to work alongside seasoned masters who had been in the industry for decades. Through this

experience, I gained invaluable insights into casting techniques, far beyond what any classroom could offer.

Realizing that I couldn't sustain this job indefinitely, I eventually transitioned to teaching and sharing my skills with students. Over the course of about a decade, I had the opportunity to

teach art at various colleges and universities across the country. Alongside my teaching endeavors, I pursued my own artistic development and obtained my MFA from the School of the Art

Institute of Chicago, marking the culmination of my academic journey. Today, I only devote myself entirely to my artistic practice, dedicating all my time and energy in the studio.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

AYA: It is interesting that you’ve mentioned the time at the foundry working with the industrial masters who are not part of the academia, even not part of the “elite” world. To view the trajectory in retrospect, do you think the training of a sculptural artist is fundamentally against elitism – something we see rampant today in art education and art criticism? And in this sense, do you think there’s anything special about the role a sculptural artist plays in the art world in general?

ANDREW: Paradoxically, for me, it’s evident that the training and ethos of a sculptor can both challenge and perpetuate elitism within the art world.

On one hand, sculptural training often emphasizes craftsmanship, materiality, and physical labor, fostering inclusivity and accessibility to individuals from diverse backgrounds. This hands-on

approach democratizes art-making, grounding it in the tangible creation rather than abstract concepts. By valuing the labor of the hand and the authenticity of material engagement, sculptors

historically blurred traditional distinctions between intellectual and manual work, challenging elitist attitudes rooted in notions of artistic superiority.

However, it's essential to recognize that contemporary sculptural practice encompasses a wide spectrum of methodologies and ideologies. While some sculptors may prioritize craftsmanship and

labor, others may explore conceptual or abstract approaches that do not necessarily challenge elitism. In fact, the emphasis on traditional craftsmanship in some contexts may reinforce elitist

attitudes by valorizing certain forms of artistic labor over others, excluding artists working in non-traditional mediums or exploring conceptual themes.

It’s hard to dedicate a specific role to sculptural artists even under the topic of anti-elitism. As any other medium, sculpturing is an evolving practice, and the evolving nature means that

we are continually navigate diverse influences and perspectives. While some may resist elitism by emphasizing accessibility and authenticity, others may perpetuate it by adhering to

traditional hierarchies and modes of production. Ultimately, the relationship between sculpture and elitism is complex and multifaceted, and it is a reflection the nuanced nature of artistic

discourse and the ever-evolving role of sculpture in contemporary society.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

The Physical Mechanism is my Oyster

AYA: Throughout your oeuvre we constantly encounter the motifs from the consumerist society – the paper tower, the plastic food container, and very counterintuitively, they are cast in iron,

bronze, plaster – materials that tend to stand long against time. In other words, it seems like you’re eternalizing what’s highly disposable in daily life.

What is the intention between creating such a tension between disposability and eternity? And, if this tension is manifested through the tension between a sculpture’s form and a sculpture’s

material, do you think this tension is what sets artistic sculpturing apart from industrial sculpturing?

ANDREW: Thanks for bringing that up, and let me answer them one by one. First, as in my work, the tension between disposability and eternity is a deliberate exploration of consumer culture's

impact. And I tried to achieve this through casting everyday objects into durable materials like iron, concrete, bronze, steel, and plaster. By immortalizing ephemeral objects in enduring

materials, I try to challenge perceptions of value and transience, prompting viewers to reconsider their relationship with commodified goods. I hope this transformation can not only challenges

disposability but also complicate it, as the sculptures themselves endure, defying the temporality associated with disposable objects.

I do think there’s a different attitude towards material when it comes to industrial sculpture-making and artistic sculpturing. At some point, I feel that as an artist, my job is almost like a

translator, stuck in between these objects and materials; all of which have their own languages and presenting to an audience of those who interpret them and understand them in very different

ways depending on their backgrounds. Unlike industrial sculpture, which may prioritize efficiency and replication, at least for me I’d like the aforementioned pieces to embrace complexity,

ambiguity, and the interplay between form and material under the lens of art history and all the pioneers that preceded my work.

I believe for me and for many of my peers alike, the juxtaposition of disposable forms with permanent materials serves as a focal point, allowing for a nuanced exploration of societal values,

environmental concerns, and human experiences. The tangled, non-economical considerations towards the materials will make a sculpture innately non-industrial – if we mean industrial in the

sense of mass-production, of a cult for efficiency.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

AYA: Apart from the tension between form and material, another set of intense tension in your work seems to be imposed by physical mechanism. In your signature work “Whispers from the Bough”

we see a cast glass weight sitting dangerously tilted on a thin bough, evoking the motion of an immediate falling down. And the similar tension we can also notice in the works featuring

banana, stones, blocks, etc. In all these series, your work functions like an agent stirring a motion in a still space, but yet, not delivering the motion in its fullness. So the motion is

evoked, but not performed - a very dangerous provocation towards the physical rule.

Physical rule seems to be something you’re always challenging in your work. Physical mechanism, the physical limitations of a material (considering the process of casting glass, you’ve pushed

the material to the very verge of breaking.) What is the intention behind this challenge? Are you tired of the reign of physical law and desiring to know, to trespass the limit? Are you trying

to create a counter-reality as against the physical law employing artistic imagination?

ANDREW: I think a little bit of all of that. The exploration of physical mechanisms and natural laws in my work stems from a deep-seated fascination with materiality and process, coupled with

a desire to engage with their inherent rules and mysteries while also seeking opportunities to manipulate and refine them. As a sculptor priding myself with a plethora of skill sets, I possess

a broad understanding of materials and processes, enabling me to strategically manipulate them at various stages of creation. I deliberately challenge rules and expectations, often subverting

the intended purpose of objects to create unexpected outcomes. My practice often finds itself centered around uncovering the latent potential within objects through material exploration and

reimagining their significance in new contexts.

In pieces like "Whispers from the Bough”, “Tether”, “Lineage” and others that deal with balance, I enjoy creating tension and instability beyond the original object's static nature. By

infusing apparently inert objects like twigs and branches with strength through mediums such as cast bronze, viewers engage instinctively, challenging their understanding of reality. This

further exemplifies what I call “the potential of the object”.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

In other works, I push the limits of what materials can achieve through their masking. I prefer to maintain the rawness of materials throughout my process; bronze remains unadorned, aluminum is left untouched, and glass is kept clear and uncolored. I believe in allowing materials to speak for themselves rather than masking their inherent qualities and pushing towards pure trompe l'oeil. I am fascinated by exploring how objects can adopt new identities when translated into materials that bear similarities to their original form but differ vastly in terms of material composition. Take for instance my piece 'Bounty Hunter,' where I cast a paper towel roll in solid, milky plaster. The result, when seen in person, challenges your perception as a viewer as you may mistake it for a real paper towel roll, only to discover it is indeed a 25lb solid sculpture if they pick it up.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

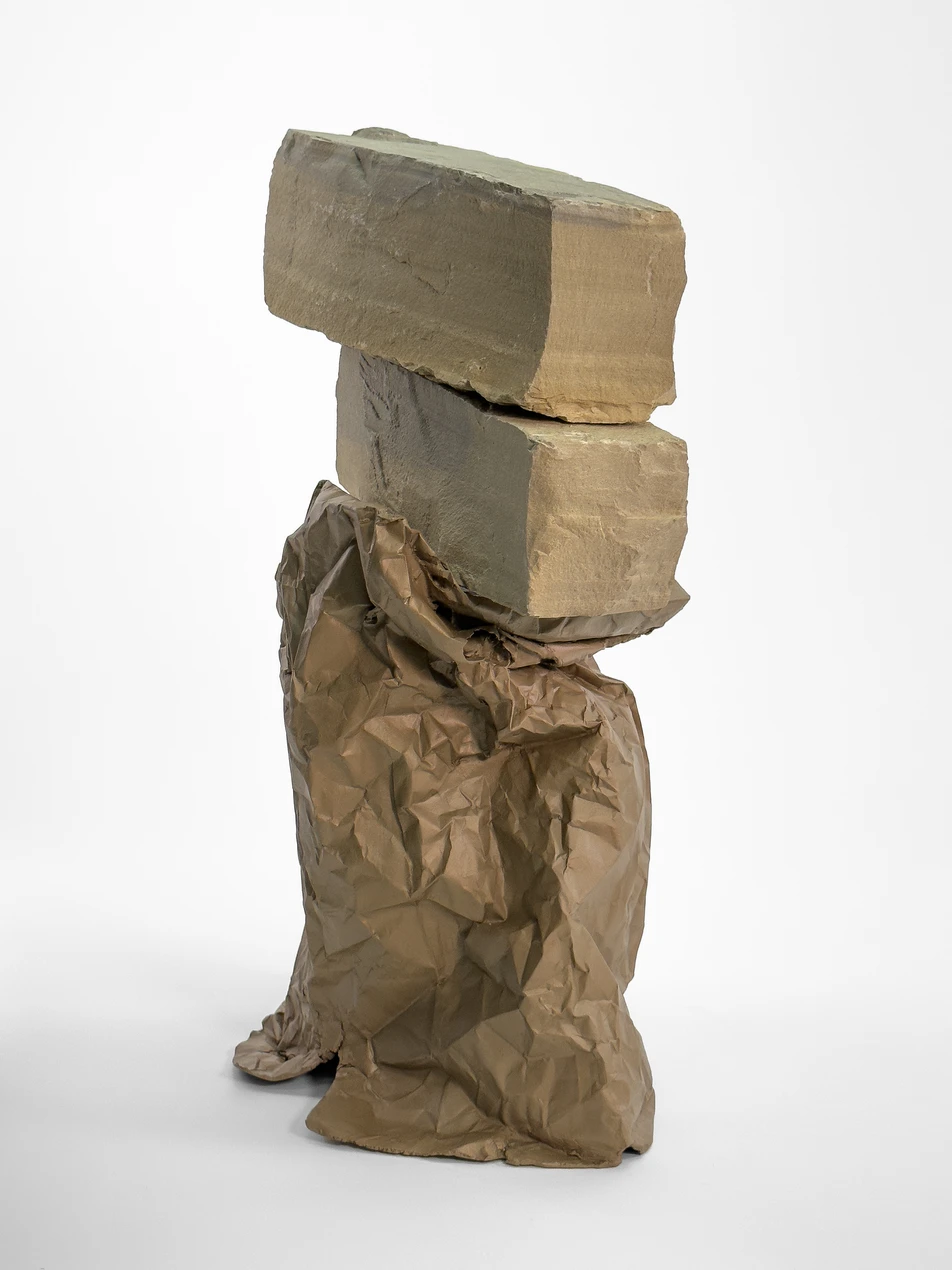

Similarly, in works like “It Remembers” and "An Alpine Song," I leave bronze untreated, appreciating how its natural color resembles that of a delicately thin brown paper bag. I'm also deeply

interested by capturing ephemeral moments that occur in an instant, like deflation, crumbling, breaking, or kicking-in. I then immortalize these fleeting gestures by casting them in durable

materials, further emphasizing my belief in finding poetics between the ephemeral and everlasting. It's about seizing a split-second moment and preserving its motion for a lifetime.

The realm of art offers an incredible canvas for exploration, enabling me, as an artist, to weave narratives that seamlessly merge reality with imagination. This distinct capability to infuse

fiction with fragments of truth stands as a testament to the transformative power inherent in visual art. Years of dedication have honed my processes and material knowledge, uncovering new

depths within the daily routine of my studio practice. Yet, the allure lies in the knowledge that there is always more to uncover, driving me to expand my vocabulary through each new piece.

That’s an exciting place to exist.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

AYA: If material is the core of sculptural art, is digital its very opposite? Can you see your sculptural work become partially or purely digital in the future?

ANDREW: The relationship between materiality and digital technology in sculptural art is multifaceted, and digital forms such as animation, virtual reality experiences, projection mapping, and

NFTs offer alternative avenues for artists to work in, prioritizing immateriality over physicality. While traditional sculptural practice emphasizes the tactile manipulation of materials,

digital tools introduce new methods of creation and expression, representing a distinct yet integrated aspect of contemporary sculptural practice. I wouldn't firmly assert that digital art

stands in direct opposition to traditional material-focused sculpture. The digital realm possesses its own sense of materiality, albeit one that is not physically altered or manipulated.

Instead, this sense of materiality is felt in a more metaphysical sense, existing within the digital space rather than the physical world.

In my own practice, while I primarily engage with physical materials, I recognize the potential of digital forms to expand the boundaries of sculptural art. Similarly, In the casting process,

objects often become "ghosts" as they are burned away or melted only to be made physical again, similar to the transient nature of digital work where creations can vanish or transform with the

click of a button but reappear in new forms with a few more clicks.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

Although I have not extensively explored digital techniques in my practice, I am intrigued by their possibilities and see them as complementary to traditional methods. Technologies such as CNC

machining, 3D scanning, and 3D printing offer precision and efficiency, allowing artists to push the boundaries of form, scale, and complexity in their work without replacing traditional

craftsmanship. Similar to how photography was initially perceived as a disruptor to painting in the early 1900s but ultimately enhanced the language of painting, we are witnessing a comparable

evolution with 3D scanning and printing today. These technologies enrich rather than erase the existing artistic landscape, offering new dimensions of exploration and expression. I think of

them as an extension of mold making, taking impressions of our natural world with the aim to translate them into new symbols.

On top of all this, advancements in my own direct processes, such as advanced casting methods and mold making, are revolutionizing traditional processes. Refractory materials are continuously

being refined to enhance usability, while metallurgical compositions of metals are evolving to increase flux and castability, resulting in higher quality finishes. Mold making materials are

also undergoing advancements to facilitate easier application in various forms, streamlining the mold-making process and contributing to overall improvements in sculptural production. So, even

in time honored processes like my own, we're still witnessing continual technological advancements that enhance and refine them.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

Humor with an Expense

AYA: In the series with motifs of plastic food container and luxury brands, there seems to be a sarcasm, a mockery, and an attempt at sharp humor. How does humor work in sculpture? And what is the genealogy of a “humorous sculpture”?

ANDREW: Humor in art is an intricate yet versatile phenomenon that operates on various levels, from subtle wit to biting satire. In my practice, I leverage it as a tool to engage viewers,

prompting them to interrogate established notions of value, consumerism, and cultural identity while sometimes having a laugh at their own expense. Perhaps a sort of self depricating humor in

an oddly sadistic way.

Throughout art history, humor has served as a compelling instrument for artists. Renaissance masters like Michelangelo and Donatello infused their works with elements of wit and irony,

endowing them with both aesthetic beauty and intellectual depth. In the modern era, artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Claes Oldenburg expanded the boundaries of sculpture by integrating

everyday objects and absurd juxtapositions, challenging established notions of artistic value and significance.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

In my own practice, humor plays a central role in addressing contemporary issues, particularly concerning modern symbology and objects. Recent works like 'Urn' and 'The Velvet of Neglect'

delve into the intricate relationship between materiality and object symbolism. 'Urn' depicts a cast iron rendition of a Gucci box, intentionally rusted over the Gucci lettering, while 'The

Velvet of Neglect' showcases a rusted takeaway container with the words 'Have A Nice Day.' These pieces serve as reflections on consumer culture and the commodification of identity, employing

humor as a means to prompt viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about society and their role in systems of power and exploitation while also expanding upon my exploration of materiality.

Iron, for instance, exhibits a dual nature; it can endure the passage of time, yet it can also rust and deteriorate. I harness this inherent quality of the material while juxtaposing it with

themes of cultural decay. In doing so, I aim to serve as a mediator between the identity of the object, the language of the material, and cultural interpretation.

Ultimately, the genealogy of humorous work is rooted in humanity's innate inclination to find levity in our surroundings. However, beneath the veneer of laughter lies a profound seriousness,

as humor often serves as a conduit for revealing uncomfortable truths and social commentary. In my practice, I aim to harness the power of humor to provoke critical reflection and dialogue,

challenging viewers to reconsider their assumptions and perceptions about the world around them and I am always trying to find a way to do this with my materials and processes.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

AYA: Tell us about some sources of inspiration we’re not expecting.

ANDREW: Traveling has always been a significant part of my life, with many frequent trips all throughout China in recent years proving particularly influential. Studying Mandarin for the past four years has broadened my cultural and linguistic horizons, directly impacting my practice. I enjoy immersing myself in various cultures, drawing inspiration from the contrasts and connections. I'm fascinated by how different cultures respond to disposability and interpret the language of materials and objects, which I constantly bring into my studio.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

You might not expect it, but I am also an avid badminton player, and it has even influenced a piece or two of mine. While my series 'The Heresy of Zone Defense' might suggest basketball as my

primary sport of interest, pieces like 'Without Exile,' which feature bronze cast shuttlecocks, reveal my deeper interests.

And lately, I've been finding inspiration literally right in my own backyard. Gardening has become a newfound passion, and I've been building a cactus garden around my studio for the past few

years. It's a peaceful retreat that I hope will continue to flourish alongside my artistic endeavors in the years to come.

Image provided by Andrew Orloski

Andrew's Past Exhibitions

SELECTED SOLO & TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS

2023 - "Bounty Hunter", Gallery Nosco. Brussels, Belgium

2023 - "Memory Echoes", Lorin Gallery. Los Angeles, CA, USA

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2024 - "SP Arte" fair, with Gallery Nosco. São Paulo, Brazil

2024 - "Daydream", Guy Hepner Gallery. New York City, NY, USA

2024 - "Swish", Zepster Gallery. Brooklyn, NY, USA

2023 - "Sexy XMas", The Lodge. Los Angeles, CA, USA

2022 - "Untitled Art" fair, with Gallery Nosco. Miami Beach, FL, USA

2022 - "Sexy Xmas", The Lodge. Los Angeles, CA, USA

2022 - "Naked Lunch / Spring Break" Curated by Giovanni Aloi. New York, NY, USA

2022 - "Rebuilding Avant-Garde", Park Across the Street Gallery. Matawan, NJ, USA

2022 - "Art Monte Carlo" fair, with Gallery Nosco. Monte Carlo, Monaco

2022 - "The Potential of Objects", MFA thesis", SAIC Galleries. Chicago, IL, USA

2022 - "The Little Thing That Counts", Gallery Marra/Nosco. Brussels, Belgium

2021 - "Untitled Art" fair, with Gallery Nosco & Marra/Nosco Gallery. Miami Beach, FL, USA

2021 - "Stargazers", Peripheral Space. Los Angeles, CA, USA

2021 - "Artissima" fair, with Gallery Nosco. Torino, Italy

2021 - "SWAB" fair, with Gallery Nosco. Barcelona, Spain

2021 - "Enter Art" fair, with Montoro12 Contemporary Art. Copenhagen, Denmark

2021 - "The Kinder Garden", Gallery Nosco. Marseille, France

2021 - "Chiller", Night Club Gallery. Minneapolis, MN, USA

2021 - "Made in California", Brea Gallery. Los Angeles, CA, USA